When Dr. Selene Gisil gets a call from the China Lake Precinct Police, she knows that it can only be about one thing: Rose House. She is the unwilling heir to Rose House, the last, greatest, strangest home designed by legendary architect Basit Deniau and imbued with a sentient, computer consciousness that controls everything about the house. In his will, Basit stipulated that nobody would be allowed inside Rose House. Nobody from among the ravening hordes of press and architects and students will ever see the papers and designs that Basit left behind—nobody except Selene. For seven days each year, Selene has permission to go inside Rose House and write her own notes about what she finds inside, though she may not take photographs or make copies.

Selene broke with Basit Deniau years ago, denouncing him as an elitist trying to reserve beautifully designed spaces for the wealthy few. Now, because of this strange legacy, she’s tethered to him forever—and that’s before she answers her phone and learns that a dead body has been found inside the walls of Rose House. The AI that runs/is the house has reported it to the police per legal requirements, and the police require Selene’s presence to get inside the house to investigate. After all, it should have been impossible for anyone (except Selene) to get into the house in the first place. Rose House should not have allowed it.

For her part, Detective Maritza Smith does not want to deal with the bother that is Rose House. But a man has died, and he died in her precinct, and she’s the person who picked up the phone when Rose House called. It’s her case, and her problem to figure out, however little she wants to. However much she fears that she won’t be able to convince Rose House to let her in the doors, or let her out again when she’s finished.

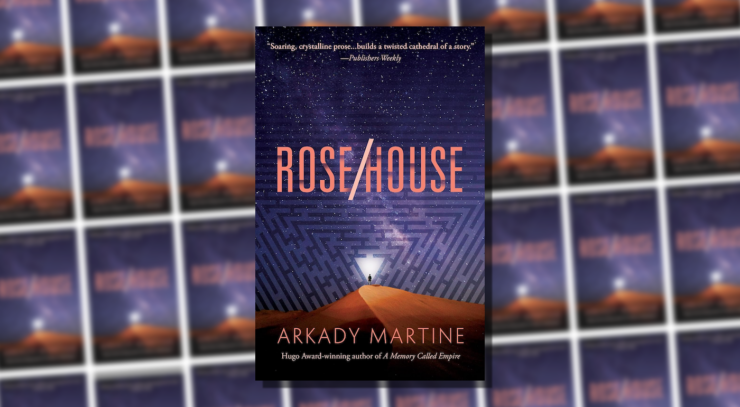

Buy the Book

Rose/House

The best trick of Rose/House is the allure and danger of the house itself, but even more so, of the idea of the house, and the house’s ideas. (Basit’s ideas.) Maritza’s able to convince Rose House to let her inside to investigate by arguing that she’s not a person at all, but an entity: China Lake Precinct. It’s the creepy version of the “there’s no rule saying a dog can’t play basketball” argument, and Maritza’s keenly aware that she’s been allowed inside on sufferance. Even so, and even recognizing that the house is the only known witness to the man’s death, she starts to enjoy matching wits with the house, finding ways to phrase her inquiries to elicit usable responses:

“Rose House,” she asked, “which cabinets are interesting?”

This time the silence was the opposite of absent. Maritza could almost feel Rose House thinking, deciding. (It decided faster than any human being—any pause was for effect, she knew it, and still. Still.) At last it said, “Interesting to the China Lake Precinct, or interesting in general?”

“The China Lake Precinct can decide for itself what it finds interesting,” Maritza said. “Interesting in general, Rose House.”

You can see why Maritza starts getting into it. Talking to Rose House like this is fun the way a puzzle video game is fun, as you dig into the assumptions you’ve made about how things work, and think laterally to figure out ways around them. At the same time, the house’s true danger starts creeping in around the edges. Just as Basit found a way to take up permanent residence in Selene’s life, even after she pronounced herself finished with him, Rose House uses its rules to subtly shift the way people think. Twice in the book, characters recognize that they’re starting to think and speak like Basit.

In her previous books, A Memory Called Empire and A Desolation Called Peace, Arkady Martine explored the ways in which imperial powers begin to colonize the mind as well as physical spaces. Rose House fulfills a similar function here, its beauty and mystery and unknowability serving as the lure to bring people like Selene and Maritza into its orbit, into its desires. Unlike Selene, and somewhat unlike Maritza, Rose House recognizes its own limitations. When it cannot win a game, it changes the game. If it realizes that it will be unsuccessful in colonizing a mind—if, say, a human detective (not allowed in the house) acting as a non-human entity (allowed in the house) comes across evidence that shifts her attitude toward the house and its rules—it reverts to other plans. The house and its maker haunt the minds of those in its orbit. As is often the case with ghosts, a haunting can become physical, violent, if the ghosts are made angry.

Perhaps not surprisingly for a book about a house that can think, Rose/House is a very unembodied book—by which I mean, it is a book that does not ask its readers to believe that its characters live inside of bodies. Scientists of animal cognition make the argument that it’s like something to be a bat, or a whale, or a dog; but we cannot know what it’s like, because we only have our own minds to think with, minds that reside inside of very specifically human bodies.

Rose/House assiduously avoids considerations of the body (as does, probably, Rose House the character). If it’s like something to be a house, distinct from what it’s like to be an asshole superstar architect, we don’t hear much about it. We know, and learn, that the house exists not to be touched and to protect its own one-ness, but we don’t know what it makes of bodily intrusion by Selene, or the dead man, or the cops in the form of Maritza Smith. Basit Deniau chose for his ashes to be compressed into a diamond that was then to be left at the heart of Rose House, and this diamond is described, again and again, as a corpse, an equivalent thing to the body whose death Maritza is investigating. Even when we see a character fleeing for their life, that escape exists on the level of the aesthetic and the intellectual—not the physical. At times, this can sap the juice of the story, setting the reader at a distance from the characters. The book’s most effective moment, not coincidentally, is also its most shockingly physical. If Rose/House is more interested in being clever than visceral, it’s still a cracking good read, bristling with hidden motives, untrustworthy tech, and questions of autonomy, selfhood, and legacy. It’s a haunted house story like no other I’ve read before: In China Lake Precinct, the house haunts you.

Rose/House is available from Tordotcom Publishing.